A proposed bill seeks to address high school dropout rates by putting the education plans in the hands of Tribes. Supporters say Tribal education compacts could lead to drastic improvement in education for Alaska Native communities.

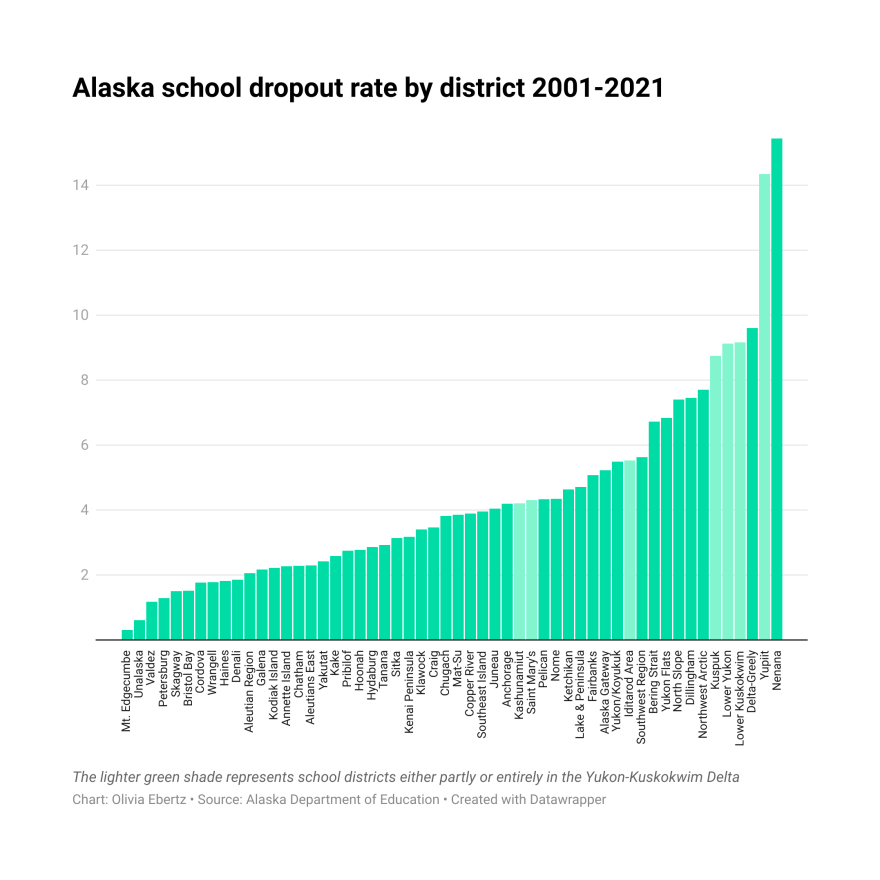

Alaska ranks among the bottom states for graduation rates. And within the state, Alaska Native students drop out of secondary school at higher rates than their peers. According to data from the past three decades, Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta schools consistently have the highest dropout rates in the state. Proponents of a new bill think that they can change poor outcomes for Alaska Native students by putting education directly in the hands of Tribes.

Senate Bill 34 would create a pilot program for Alaska Native Tribes to begin running their own public schools through a compact agreement with the State of Alaska.

The Alaska Federation of Natives collaborated with the state on the bill. AFN wants the state to allow five schools to be included in an initial demonstration project. After five years of funding, the state would reassess what’s working and what’s not. But right now, AFN president Julie Kitka says it’s clear that the Western-centric model isn’t working.

“The state and the commissioners are saying that the state is failing Native students right now,” said Kitka.

Hooper Bay Elder William Naneng also supports the Tribal education compacting bill.

“Our people and our parents want to learn, they want to see the students excel. They want to see our people are going to school, they're being very curious,” said Naneng.

Naneng serves on the board of a new charter school in Hooper Bay. The school’s curriculum is centered around Yup’ik values, called yuuyaraq. He hopes that the state will choose his school in the first round of demonstration projects.

Naneng said that years of imposed, colonial Western education in Hooper Bay has led to poor outcomes for students. He says he only attended school because his parents were afraid he’d get taken away. He wasn’t allowed to speak Yup’ik in class. He says practices like these have led to low graduation rates in the Lower Yukon School District (LYSD). LYSD’s graduation rates are among the lowest in the state. He worries this makes it look like Yup’ik people don’t care about education, but he said that couldn’t be further from the truth. He said that Yup’ik people literally survive through education, but theirs is different from Western education.

“We're taught as, like, life and death situation. Things that we needed to know in order to survive and do very well in the environment that we live in,” said Naneng.

In order for students to succeed, Naneng said that they need to be taught in ways that are relevant to their lives. That’s why he says the education should be placed in the hands of the Tribe.

And Kitka said that she hopes a culturally relevant education can lead to better outcomes for Native students.

“Greater attendance, greater life skills, greater community support, parent involvement, greater teacher recruitment and retention, all components that make a healthy school,” said Kitka.

The Alaska Department of Education’s Tribal liaison, Joel Isaak, has been advising the state on what the bill should look like for Alaska Native communities.

Isaak said that the bill was carefully crafted to allow schools to do just what Naneng is asking for: create curriculums and schedules that work for each individual Tribe. If this bill becomes law, Tribes will be able to restructure their school years around subsistence activities and create their own curricula.

“Alaska is not a monolith. And there's no one clear education model for all Alaska Native peoples, that's not the case,” said Isaak.

The schools would still need to match education standards and classroom hours set by the state and have state-certified teachers, but other than that, the Tribes could implement whatever they want.

Isaak said that this bill is modeled, in part, on the success of a similar program in the state of Washington. Washington has three Tribal-compacted schools, and they’ve done well. According to a study done by Evergreen State University, the schools showed improvement in the following areas: graduation and retention rates, reputation, enrollment, teacher recruitment and retention, and student connection to culture.

Kodiak Sen. Gary Stevens first introduced the bill in the Alaska Senate. Bethel Rep. Tiffany Zulkosky sponsored the House version. Zulkosky also chairs the Tribal Affairs Committee and serves on the House Education Committee.

Zulkosky said that Tribes have great infrastructure and ideas in place to help support compacting projects. She pointed out that there’s already a good model in place for education compacting: Tribal healthcare.

“I think Tribes are a quiet, but mighty, incredible resource to providing culturally relevant services across Alaska. I absolutely am excited about this bill,” said Zulkosky.

The bill must pass through the Senate Judiciary and Finance Committees before it can be voted on the floor. If the bill is passed by both the Senate and House and signed by the governor, it will be sent to the next legislature. If the next legislature passes the bill, Tribal-compacted schools could open their doors as soon as the fall 2025.

Back in Hooper Bay, the charter school’s principal, Jamie Wollman, said that this bill will ensure funding. That will allow her to channel some of the school’s resources away from grant writing and back into the students. Plus, she said that the school will be able to contribute to the local economy. She said that this bill could allow her more consistent funding to hire local Elders to help the teachers plan their lessons.

Right now, Elders are helping plan an entire curriculum around eggs. Bird eggs in the spring and fish eggs in the summer help infuse local traditions into traditional Western teaching.

Copyright 2022 KYUK. To see more, visit KYUK. 9(MDA3ODI0NDE3MDEzMTA3MjkwNzJhOTgzNQ004))