The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act certainly has its flaws. But museums and Native cultural organizations look to the future of digital collections and repatriation.

The Alutiiq Museum, which is based in Kodiak, will begin to digitize its collection with the eventual goal of expanding and digitizing collections from other museums.

Museum collections curator Amanda Lancaster says they’re already using a database and have most of their object’s catalogued.

"We use a database called Collective Access, and they are designing. So we already have sort of the back end where we have all of our objects catalogs to some degree. And so “We'll be adding our ethnographic objects to this very specific part of the database. And then later, we'd like to add Alutiiq collections that are around the world, so there's some at the Alaska State Museum all the way to France and Finland and beyond. And so we'd like to just make all of these collections available to people to be able to look at in one central place."

(Editor's note: This story is the third of a three-part series. Read the entire series and listen to the extended podcast on repatriation at knba.org)

The database would allow people to view the collections in one central place.

"I'd like to kind of see like a map that has little pins everywhere and you can just kind of go to the pen and look and see these elliptic collections."

Lancaster says that because some items are culturally significant, the museum can put part of that collection behind privacy firewalls – so that only Tribal members could access them.

“One thing that sort of I just wanted to mention because you touched on it, is one aspect of our database that I that we designed specifically in mind,” Lancaster said. “We can sort of set privacy settings on our database. So when we make things accessible, we don't have to make them accessible to the public at large. We can make them accessible maybe just to Tribes.”

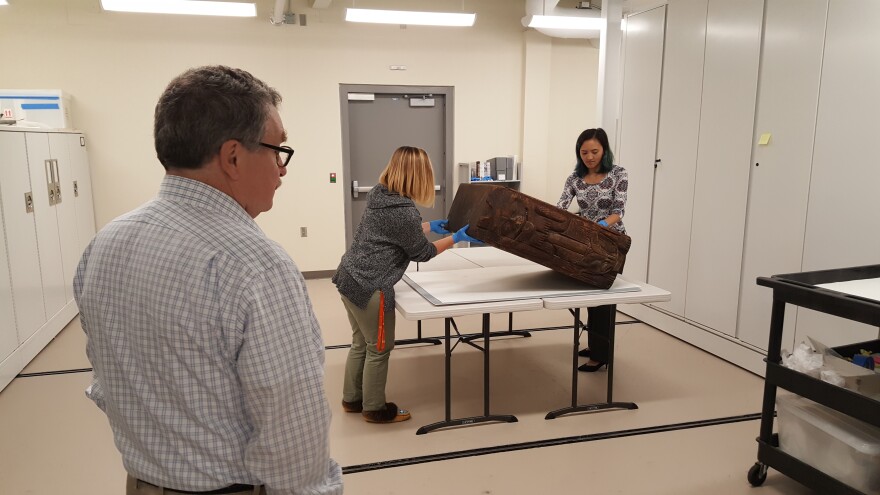

In Juneau, Sealaska Heritage Institute began a similar process that studies physical objects through photographs, electromagnetic patterns and other ways.

The process called photogrammetry allows for three-dimensional documentation of cultural objects, such as carvings, which can be studied in-depth and remotely. The technology could potentially make older pieces held by museums available to artists around the world who might otherwise not have access to the work, SHI director Rosita Worl said.

"It's really time consuming and hopefully the technology is going to be kind of improve."

Sealaska Heritage Institute also has worked with 3-D printing to help preserve objects, as well as infrared imaging to see details obscured over time. And it brings up similar questions the Alutiiq Museum brought up on what to make available and for whom. An example of something that might be held behind a privacy wall would be images of clan crests.

Worl says that Sealaska Heritage also does a lot of work to digitize its collection.

One thing Sealaska Heritage has also fought for were items that are sold at public auction – and sometimes on online auction houses and even eBay.

In one way, NAGPRA has inspired multiple pieces of legislation.

Worl says one piece of legislation she’s working on would stop the export of sacred objects overseas.

“And then another piece of legislation that we have in Congress or before Congress is a tax incentive act where … tax legislation wvould give additional benefits to the collectors for returning objects to."

Currently many collectors want to sell items and organizations like Sealaska Heritage may not be able to raise enough money to buy the item. And there’s nothing to incentivize the collector to donate the item at a so-called “loss.”

But the legislation would be able to give the collector more compensation for donating an item back to a Tribe or Tribal organization.

But in regards to the current laws on the books as they pertain to museums, Worl says she thinks museums are changing for the better.

“Some of these museums like Peabody Essex are trying to follow the social movement that we are seeing in the country, not everywhere, but certainly it is a social movement where equality and the rights of minorities and Indigenous people are being at least are saying they have rights. And so that's progress.”

She also sees change in younger museum professionals.

“My colleagues are the old guys, and they are just totally opposed to repatriation and NAGPRA,” Worl said. “But I'm seeing the younger generation of museum professionals that are much more understanding and accepting of a Native American belief system.”

Worl says she rewatched footage of a ceremony honoring the return of a 100-plus-year-old Chilkat blanket in 2017. And she wanted to share that video with other museums and historians.

“I think it really exemplified how we feel, how we see how we see things differently, how material objects can you have spirit.”

During that ceremony a Seattle couple returned the robe to Sealaska Heritage Institute. The exact origins of the blanket were difficult to determine, and Chilkat weavers planned to study the robe to see how it was made.